History

Hawaiian Princes Surfing Santa Cruz: How 3 Royals Introduced Surfing to the Continent on Redwood Boards

The Hawaiian Princes Who Pioneered Surfing in Santa Cruz

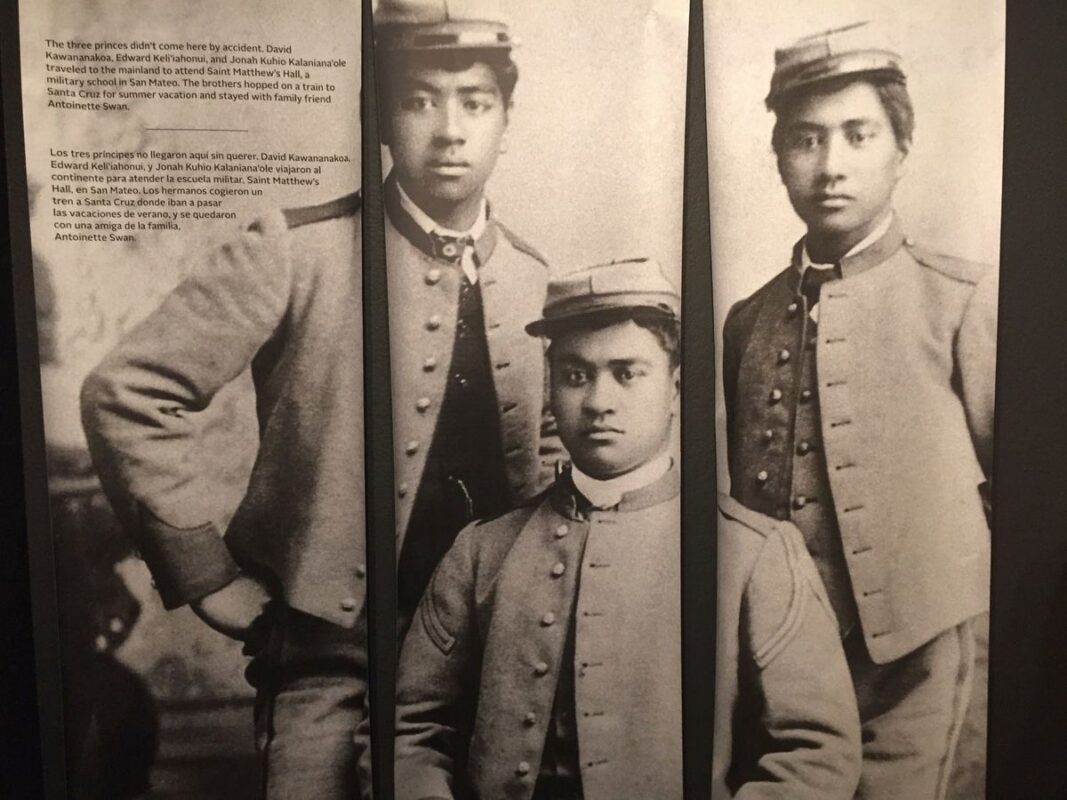

In the summer of 1885, long before surf shops lined the beaches and fiberglass boards dominated the lineup, three teenage Hawaiian royals changed the course of wave-riding history. These weren’t just any surfers—they were princes David Kawānanakoa, Edward Keliʻiahonui, and Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, nephews of King Kalākaua. Sent to study at a military academy in California, they spotted familiar swells at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River in Santa Cruz and decided to show the mainland what true Hawaiian princes surfing Santa Cruz looked like.

Crafting Redwood Boards for Surf Diplomacy

Armed with custom o’lo boards crafted from local redwood lumber, the princes introduced “surfboard swimming”—the original name for surfing—to the U.S. continent for the first time. The San Lorenzo River mouth, before modern jetties and harbors altered its flow, produced gentle, Waikiki-like breakers that reminded them of home. They commissioned boards from the Grover Lumber Company, milling first-growth redwood from the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains into massive o’lo shapes—up to 18 feet long and weighing 150-175 pounds each. These weren’t lightweight modern shortboards; they were finless behemoths, demanding immense skill and strength to paddle and ride.

The Historic 1885 Surf Session in Santa Cruz

On July 19, 1885, the princes hit the water, drawing crowds of astonished locals. The Santa Cruz Surf newspaper captured the moment: “The young Hawaiian princes were in the water, enjoying it hugely and giving interesting exhibitions of surfboard swimming as practiced in their native islands.” Spectators watched in awe as the brothers balanced on their redwood giants, gliding across waves with the grace of Polynesian royalty. This wasn’t just recreation; it was cultural exchange, or what historians now call “surf diplomacy.” The event was documented as the first instance of surfing on the U.S. mainland, predating Duke Kahanamoku’s global promotions by nearly three decades.

Lasting Impact of the Princes’ Surfing Legacy

The impact rippled far beyond that sunny afternoon. Locals quickly adopted the sport, with the Santa Cruz Surf noting by 1896 that “the boys who go surfing in the surf at Seabright Beach use surfboards to ride the breakers, like the Hawaiians.” The princes took their redwood boards back to Hawaii, sparking a trend: Redwood became the go-to material for Hawaiian surfboards in the early 20th century, shipped en masse from California mills. Tragically, Prince Edward passed away soon after returning, but his brothers continued spreading the aloha spirit. Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole became a U.S. congressional delegate and helped establish Hawaiian Home Lands, while David Kawānanakoa contributed to politics and culture. Their legacy? Cementing surfing’s roots in Hawaii while exporting it worldwide.

Celebrating the Princes’ Contribution Today

Fast-forward to today, and the story lives on. In 2015, two of the original redwood boards resurfaced at Hawaii’s Bishop Museum and returned to Santa Cruz for a blockbuster exhibit at the Museum of Art & History (MAH), breaking attendance records. Local shaper Bob Pearson crafted replicas, leading to paddle-outs and demos that honored the 130th anniversary—complete with a mayoral proclamation declaring July 19 “Three Princes Day.” More recently, in 2025, the MAH’s “Princes of Surf” exhibit revisited this history with gleaming replicas and evolved board displays, highlighting how those redwood o’los paved the way for modern surf tech.

Ride Like Royalty with Hawaii’s Surf Heritage

For surf enthusiasts in Hawaii, this tale underscores the islands’ unbreakable bond with the ocean. At hawaii.surf, we celebrate this heritage every day—whether you’re chasing North Shore giants or learning at Waikiki. The Hawaiian princes surfing Santa Cruz reminds us: Surfing isn’t just a sport; it’s aloha passed down through generations, connecting Hawaii’s royal past to today’s global wave culture.

(Sources: Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History exhibits, historical accounts from NPR and local archives.)