History

Sammy “Steamboat” Mokuahi: Hawaiian Wrestling Legend and Outrigger Canoe Paddling Pioneer

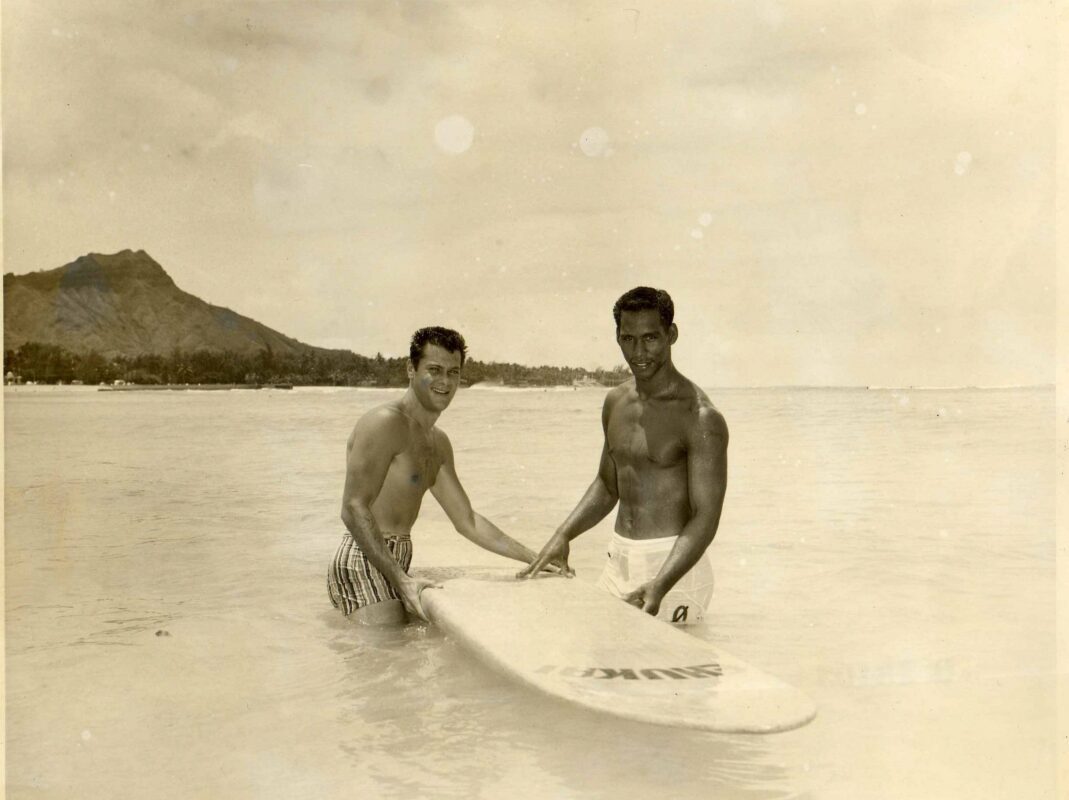

Image courtesy of Outrigger Canoe Club

Sammy “Steamboat” Mokuahi: The Hawaiian Wrestler Who Championed Ocean Traditions

Honoring a Native Hawaiian athlete who conquered wrestling rings worldwide, then returned home to preserve his culture through outrigger canoe paddling

February 2026: Celebrating Hawaiian Heritage

As we observe Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian Language Month) this February 2026, we honor Samuel “Sammy Steamboat” Mokuahi Jr., whose very name tells the story of Hawaii’s rich cultural heritage. Born May 4, 1934, in Honolulu, Sammy carried a surname that translates directly from Hawaiian: Mokuahi means “steamboat,” from moku (vessel or ship) and ahi (fire).

According to family tradition, Sammy’s great-great-great-grandfather was born on a steamship arriving in Hawaii, and his grandmother translated this origin story into the Hawaiian name Mokuahi. When young Sam entered professional wrestling in the 1950s, he simply used the English translation of his birth name, becoming “Sammy Steamboat.”

But Sammy’s legacy extends far beyond the wrestling ring. While he achieved championship success across America from the mid-1950s through the late 1970s, his greatest contribution came after retirement: making outrigger canoe paddling a sanctioned high school sport in Hawaii in 2000, ensuring future generations could connect with this ancient Hawaiian tradition.

Born to Hawaiian Royalty: The Beachboy Legacy

Samuel Kauaawa Mokuahi Jr. was born into Hawaiian waterman royalty. His father, Gabriel Kauaawa “Sam” Mokuahi Sr., known as “Steamboat” or “Big Boat,” was one of the original Waikiki beachboys during the golden era of the 1920s through 1960s. His mother was Rosalia Keaka Hulihee.

The Mayor of Waikiki

Sam Sr. earned the unofficial title “Mayor of Waikiki” for his larger-than-life presence on the beach. Born in Honolulu in 1918, he taught himself to surf as a child at Kakaako when ironing boards were used as makeshift surfboards. He started surfing at Waikiki around 1932 or 1933, becoming a lifeguard before establishing himself as one of the most beloved beachboys of his generation.

Big, strong, and bronzed from a life in the sun until well into his 70s, Sam Sr. had a gentle heart and befriended people from all over the world. He worked primarily in front of Duke Kahanamoku’s at the Outrigger Canoe Club, steering the ancient koa canoe Ka Mo’i through Waikiki’s famous surf and taking countless visitors on unforgettable rides.

Sam Sr. had supporting roles in several films made in Hawaii, including “The Old Man and the Sea,” and took celebrities like actors David Niven and Alan Ladd on canoe rides. Fellow beachboy Ken “Squirrel” Carvalho recalled, “He was a perfect gentleman. He called everybody ‘laddy’ or ‘laddy boy.’ He danced hula at my wedding.”

A Family of Givers

Sam Sr. was one of the first to offer canoe and surfboard rentals on Waikiki Beach, but he was legendary for his generosity. His nephew Kevin Mokuahi, who became a Lokahi Canoe Club coach, remembered: “If they had no money, he’d say, ‘Take the board out and bring it back.'” He would cut pieces of plywood and tell kids, “Here, take this out and catch some waves.”

Kevin Mokuahi emphasized that Sam Sr. “made everybody feel like family.” The Mokuahi family embraced both blood and hanai (adopted) relatives as part of their proud Hawaiian lineage, reflecting traditional Hawaiian values of extended ohana.

Growing Up on Waikiki Beach

Young Sammy absorbed this world of aloha, ocean mastery, and cultural pride. He had four brothers: Bernie Ching, Samson Mokuahi, Kevin Mokuahi, and Shannon Mokuahi. Growing up as the son of one of Waikiki’s most respected beachboys meant learning not just how to surf and paddle, but understanding the deeper cultural significance of these practices and the responsibility to share them generously with others.

Sam Sr. passed away in June 1998 at age 80, with his ashes scattered from canoes gathered in front of Duke Kahanamoku’s at the Outrigger Canoe Club, where he’d spent so many years as a beachboy. By then, his son had already established his own legendary status in two very different arenas.

Roosevelt High: The Foundation of an Athlete

Sammy attended President Theodore Roosevelt High School in Honolulu, where he distinguished himself as a multi-sport athlete in the post-World War II era. He played football, wrestled, and competed in various sports, developing the size, strength, and competitive drive that would serve him well in professional wrestling.

His natural athletic gifts, combined with the physical conditioning that came from growing up swimming, surfing, and paddling outrigger canoes in Hawaiian waters, gave Sammy an exceptional foundation. By the time he graduated, he stood well over six feet tall with a powerful, muscular build.

Fellow wrestler King Curtis Iaukea would later recall in February 2000: “He was the best looking man I’ve ever seen walk across the sand of Waikiki.”

From Beach to Ring: The Making of a Wrestler

Sammy’s transition to professional wrestling came through a chance encounter that would change his life. In the mid-1950s, Honolulu had become a regular stop on the professional wrestling circuit, and wrestlers loved the territory. They could work one or two days a week, earn decent pay, and spend the rest of their time enjoying Hawaii’s beaches.

The Training Begins

Lord James “Talley-Ho” Blears, a British wrestler who had fallen in love with the islands, encountered young Sammy on Waikiki Beach. “He was on Waikiki beach, he was a beach boy, but he had a terrific body on him, worked out surfing every day,” Blears recalled from his nursing home bed decades later. Recognizing Sammy’s potential, Blears made an offer: “I’ll teach you to wrestle if you teach me how to surf.”

The arrangement proved perfect. Every day, Sammy took Blears out on the board, teaching him to read waves and ride Hawaiian surf. In return, Blears took Sammy to the gym, teaching him the fundamentals of professional wrestling: holds, throws, ring psychology, and how to work a crowd.

Learning from the Greatest

But Sammy’s most important mentor was Lou Thesz, one of the greatest professional wrestlers of all time and a six-time world heavyweight champion. Thesz loved visiting Hawaii and was good friends with Sammy’s father. According to fellow wrestler Dick Beyer, “Lou Thesz had a lot to do with training him. Lou Thesz, he loved to go to Hawaii too. He was good friends with Sammy’s father.”

Thesz stated that Mokuahi was the only one he ever saw as a student or protégé. Coming from a wrestler of Thesz’s caliber, this was the ultimate compliment. Thesz emphasized technical excellence and fundamental holds, teaching Sammy: “Wrestle, do not be clown.”

Other wrestlers contributed to Sammy’s education as well. Gene Kiniski remembered: “He used to have a neck like a goddamn goose, and we used to work on his neck at the beach every day. Finally, we got his neck worked it up like it should be.”

By 1956, Sammy Mokuahi was ready to turn professional, adopting the ring name “Sam Steamboat,” the English translation of his Hawaiian surname.

The Wrestling Years: Championship Success Across America

Hawaii: The Home Territory

Sammy began his career with 50th State Big Time Wrestling, Honolulu’s premier wrestling promotion. His first championship came quickly. On August 5, 1956, Steamboat teamed with Billy Varga to defeat Great Togo and Tosh Togo for the NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship.

On January 25, 1961, Steamboat captured his first singles championship, defeating Dick Hutton for the NWA Hawaii Heavyweight Championship. Though he lost the title to Luigi Macera on April 15, 1961, Sammy had established himself as a main event talent.

The Technical Master

Unlike many wrestlers who relied primarily on power moves or showmanship, Sammy Steamboat was a technician. His training under Lou Thesz emphasized precise submissions, quick strikes, and mat wrestling. This style earned him respect from wrestling purists and made him a versatile performer.

A September 1960 newsletter dedicated to legendary wrestler Whipper Billy Watson described Steamboat’s appeal: “Sam is one of the most colourful wrestlers in the ring today and is also a fan favourite where ever he wrestlers. Why is he a fan favourite? Mainly because his fans know when he enters the ring, he possesses everything a wrestler should have, is fast as lightning, and prefers the clean scientific style.”

Fellow wrestler Danny Miller, who teamed with Steamboat in Florida in the late 1960s, recalled: “The fans loved him. He was straight-laced. He was very sincere about his work. He was a nice person, very quiet and very shy. He really was, about meeting people.”

Conquering the Mainland Territories

In the early 1960s, Sammy began wrestling on the mainland, competing in the National Wrestling Alliance’s territorial system. His first major mainland success came in Los Angeles with Worldwide Wrestling Associates. In 1960, he won the WWA International Television Tag Team Championship with Dick Hutton.

Florida became a particularly important territory for Steamboat. He aligned himself with local hero Eddie Graham, one of Florida wrestling’s most respected figures. Together they became regular tag team partners, winning the NWA World Tag Team Championship (Florida version) three times. Steamboat also won the Florida tag titles with Ron Etchison and Jose Lothario.

In Georgia Championship Wrestling, Steamboat won the NWA Southern Tag Team Championship with Eddie Graham in 1964. He competed in the Mid-Atlantic territories, winning the NWA World Tag Team Championship (Mid-America version) twice with Graham in 1965.

Sammy made tours through Toronto, Texas, and various NWA territories throughout the 1960s. Everywhere he went, his reputation as a skilled technician and genuine nice guy preceded him.

The Ricky Steamboat Connection

Sammy became such an icon in Florida that when a young wrestler named Richard Blood started in the territory in 1976, promoter Eddie Graham gave him the ring name “Ricky Steamboat,” billing him as Sammy’s nephew. Though the two men were unrelated and Ricky was actually a New Yorker of mixed Caucasian and Japanese descent, the Steamboat name had become synonymous with athletic excellence.

Ricky Steamboat told writers years later: “The Steamboat name did obviously derive from Sam. Eddie Graham and Jack Brisco when I went to Florida after I left Minneapolis, Eddie Graham gave me the name. And it wasn’t because of my work, it was only because of Sam Steamboat.”

Return to Hawaii

By the late 1960s, Sammy returned to Hawaii, where he would spend much of the remainder of his wrestling career. He won the NWA Hawaii Heavyweight Championship three more times and captured the NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship four additional times, partnering with legendary wrestlers like Bearcat Wright, Peter Maivia (grandfather of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson), and Billy White Wolf.

He also won the NWA North American Championship (Hawaii version) four times.

During the 1970s, wrestling in Hawaii reached peak popularity. The Civic Auditorium and Honolulu International Center arena regularly sold out for cards featuring Steamboat and other island heroes. Sammy was a literal household name, beloved by local fans who saw him as one of their own.

His daughter Samantha Moikeha recalled: “To different people from different eras, he was different things. To Mainland people in the 1950s, he was a big wrestler. In the ’60s and ’70s, it was Wrestling Hawaii.”

Sammy retired from professional wrestling in the late 1970s after more than two decades in the ring.

Complete Championship Record

Throughout his career from 1956 to the late 1970s, Sammy Steamboat won numerous championships:

NWA Hawaii Heavyweight Championship (4 times)

NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship (5 times): with Billy Varga, Bearcat Wright, Peter Maivia (2 times), and Billy White Wolf

NWA North American Heavyweight Championship, Hawaii version (4 times)

WWA International Television Tag Team Championship: with Dick Hutton (1960)

NWA World Tag Team Championship, Florida version (5 times): with Eddie Graham (3 times), Ron Etchison, and Jose Lothario

NWA World Tag Team Championship, Mid-America version (2 times): with Eddie Graham

NWA Southern Tag Team Championship, Georgia version: with Eddie Graham (1964)

NWA Southern Tag Team Championship, Mid-Atlantic version: with Eddie Graham (1965)

NWA Florida Tag Team Championship: with Cyclone Negro (1969)

The Water Calls: Surfing and Ocean Life

Even during his wrestling career, Sammy remained deeply connected to Hawaiian water sports. He was an avid surfer who competed in events like the Pacific Surf Games, continuing the beachboy tradition his father had exemplified.

In 1972, Sammy co-founded a surf school in Waikiki with Arthur “Buffalo” Rutledge, a legendary Hawaiian waterman. This wasn’t just a business venture but a way of giving back to the community and preserving his father’s legacy of sharing Hawaiian surf culture with the world.

Through the surf school, Sammy introduced generations of visitors to Hawaiian waves, combining his athletic background as a professional wrestler with his cultural knowledge as a beachboy’s son.

The Greatest Legacy: Outrigger Canoe Paddling

If wrestling made Sammy famous, outrigger canoe paddling became his life’s greatest contribution to Hawaiian culture.

Discovering His True Calling

After retiring from professional wrestling, Sammy shifted his primary focus to outrigger canoe paddling. This traditional Hawaiian sport involves teams of paddlers propelling long canoes across open ocean, often covering dozens of miles in races that test endurance, teamwork, and ocean navigation skills.

Sammy’s daughter Samantha noted: “In the ’80s and ’90s, it was paddling and coaching. He was always doing something.”

Coaching Success

Sammy coached multiple clubs, including the prestigious Outrigger Canoe Club, Hui Nalu (one of the original beachboy clubs), and Waikiki Surf Club. His coaching philosophy emphasized traditional techniques, physical conditioning, team unity, and deep respect for the ocean.

His most notable achievement came in 1993 when he coached Hui Nalu to the state championship. For a club with such deep historical roots in Hawaiian paddling culture, this victory represented the culmination of everything Sammy had learned and taught.

Reney Ching, who later became Hui Nalu’s head coach, said: “His word was absolute gold. He made a big impact on so many of us.”

The High School Paddling Revolution

But Sammy’s most important contribution to outrigger paddling came in his tireless work to make the sport accessible to Hawaii’s public high school students.

In 2000, thanks largely to Sammy’s vision and effort, outrigger canoe paddling became a sanctioned high school sport in Hawaii. This wasn’t just an administrative victory but a cultural milestone that ensured future generations of Hawaiian youth would have access to this ancient sport.

Ching emphasized: “He didn’t just help get it rolling; he was THE person who got it rolling. Through his vision, the high school kids now have a state championship.”

Sammy’s contribution went beyond advocacy. He spent decades building and donating dozens of canoes to public schools that couldn’t afford them. He worked with Na Opio, an organization dedicated to keeping paddling alive in public schools, literally crafting the vessels that would allow the next generation to experience this Hawaiian tradition.

Former Na Opio President Teddi Anderson said: “He was a hanai dad to me. Without him there would be no paddling in public high schools or state championship. There are so many canoes out there that have his signature on them that I couldn’t begin to count.”

In March 2006, just months before his death, Sammy was honored at the fifth state high school championship for his contributions.

Why Paddling Mattered

For Sammy, promoting outrigger canoe paddling was about cultural preservation, community building, and providing young people with positive activities that connected them to their Hawaiian heritage.

His daughter Samantha reflected: “Of all the things he did, I think he enjoyed working with the kids the most.”

Paddling taught discipline, teamwork, physical fitness, and connection to Hawaiian traditions. For Sammy, who’d grown up as a beachboy’s son and traveled the world as a wrestler, giving back to Hawaiian youth through paddling was the most important work he could do.

A Gentle Giant: Character and Family

Throughout his life, whether in the wrestling ring or steering an outrigger canoe, Sammy embodied the values his father had demonstrated on Waikiki Beach.

Large Man, Gentle Soul

Physically imposing at well over six feet tall with the muscular build of a professional wrestler, Sammy was “a large man with a gentle soul,” as one obituary described him.

Lord James Blears emphasized: “He was a nice person, very quiet and very shy. He really was, about meeting people.”

Friends and family described Sammy as someone who helped people quietly, without seeking recognition. His daughter Samantha said after his death: “We knew he did a lot of stuff, but he did it quietly. He’d help people on the street, take in stray animals. Nothing we hear about seems out of the ordinary, but it’s on a scale much bigger than we thought.”

After Sammy’s passing, the family’s phone rang nonstop with people sharing stories: “Your dad did this for me,” or “I’ll never forget the time…” Each call revealed another act of kindness, another life touched.

The Perennial Good Guy

Like Richard Blood, aka Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat, who inherited his name and legacy, Sammy Steamboat was a perennial good guy. It wasn’t an act. His reputation for kindness and genuine concern for others was consistent whether cameras were rolling or not.

Family

Sammy married Sheryll, and together they raised seven children: Samantha Moikeha, Sabrina Mokuahi, Micah Mokuahi, Mekea Leoiki, Kapena Mokuahi, Jessica Keys, and Mitchell Mokuahi. Despite the demands of his wrestling career and later his coaching commitments, Sammy remained devoted to his family.

By the time of his death, Sammy had become a grandfather twelve times over.

Hawaiian Values: Living the Culture

Throughout his life, Sammy maintained a deep connection to his Native Hawaiian heritage and actively worked to preserve and transmit Hawaiian culture to future generations.

Core Hawaiian Principles

Sammy embodied essential Hawaiian values in his daily life:

Aloha: The spirit of love, compassion, and generosity that defined his interactions with everyone he met.

Ohana: His expansive definition of family that included blood relatives, adopted family, friends, and the entire community.

Malama: Caring for the ocean and the people around him, demonstrated through his work with youth and environmental stewardship.

Kuleana: Understanding his responsibility to preserve and pass forward the traditions he’d inherited from his father and previous generations.

The Mokuahi Name

The Mokuahi name itself carried deep significance. As Sam Sr. explained, his great-great-great-grandfather was born on a steamship coming to Hawaii, and his grandmother had translated this origin story into the Hawaiian name Mokuahi (steamboat).

For Sammy to use “Steamboat” as his wrestling name wasn’t just convenient but a way of honoring his ancestors and maintaining his Hawaiian identity even while achieving success in a mainland-dominated sport.

As Kevin Mokuahi explained: “All those who carry the Mokuahi name are proud of it, whether they are hanai or blood-related. He made everybody feel like family.”

The Battle with Alzheimer’s and Final Days

In his later years, Sammy faced Alzheimer’s disease. Fellow wrestler Dick Beyer visited Sammy and his wife Sheryll in 2004: “He was just at the start of Alzheimer’s,” Beyer recalled sadly.

For someone whose identity had been so deeply tied to physical prowess and mental acuity, the disease represented a profound loss. But even as Alzheimer’s progressed, Sammy’s fundamental kindness remained.

Passing of a Legend

On May 2, 2006, Sammy “Steamboat” Mokuahi died at his Hawaii Kai home from complications of Alzheimer’s disease, two days shy of his 72nd birthday.

News of his death sent ripples through multiple communities. Wrestling fans who remembered his matches mourned. Paddling communities across Hawaii grieved for their champion. And hundreds of people whose lives Sammy had touched quietly reflected on the kindness he’d shown them.

“The number of people he has touched is way beyond my counting ability,” his daughter Samantha said, overwhelmed by the outpouring of tributes.

Memorial Service

On May 20, 2006, a memorial service was held at Maunalua Bay Beach Park. The family specified that attire was “whatever you feel comfortable wearing” because “that’s what Dad wanted.” This informality reflected Sammy’s unpretentious nature.

The memorial began with an 8 a.m. visitation followed by a 10:30 a.m. service. Then, in traditional Hawaiian fashion, a flotilla of canoes accompanied the scattering of Sammy’s ashes beyond the reef at Maunalua Bay. It was a fitting farewell for a man who had dedicated his life to preserving outrigger paddling.

Dick Beyer tried to arrange travel from the mainland to attend, testifying to the genuine friendships Sammy had built throughout his wrestling career.

Sammy’s death came just eight years after his father Sam Sr. had died in June 1998 at age 80. Now father and son had both returned to the Hawaiian waters that had given them so much.

The Waikiki Beachboy Era: Historical Context

To fully appreciate Sammy’s legacy, it’s essential to understand the unique historical moment his father helped create.

The Revival of Surfing

When Sam Mokuahi Sr. began surfing in the 1930s, he was participating in the revival of an ancient Hawaiian sport that Christian missionaries had nearly destroyed. In the 19th century, missionaries dismissed surfing as “idle amusement” and “pagan ritual.” By the 1890s, when Duke Kahanamoku was born, only dozens of surfers remained where once there had been thousands.

The Waikiki beachboys of the 1920s through 1940s saved surfing from extinction. Duke Kahanamoku, Sam Mokuahi Sr., Albert “Rabbit” Kekai, Charles “Panama Dave” Baptiste, William “Chick” Daniels, and others not only kept surfing alive but shared it with the world, turning it into a global phenomenon while maintaining its Hawaiian cultural roots.

Tourism and Cultural Exchange

The beachboys represented Hawaii’s first major tourist industry workers. When the Moana Hotel opened in 1901 and the Royal Hawaiian followed in 1927, wealthy celebrities and tourists flocked to Waikiki. The beachboys welcomed them, taught them to surf and paddle canoes, entertained them with ukulele music and hula, and gave them authentic experiences of aloha.

This cultural exchange was complex. The beachboys were preserving Hawaiian traditions while also making them accessible to outsiders. They navigated the tension between hospitality and cultural appropriation, between sharing and exploitation.

Men like Sam Sr. managed this tension gracefully, maintaining Hawaiian values while building economic foundations that would support their families and communities.

The End of an Era

World War II and the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 transformed Hawaii forever. Martial law disrupted Waikiki’s carefree lifestyle. The postwar boom brought mass tourism, larger hotels, and commercialization that changed the intimate beachboy culture.

By the time Sammy was coaching paddling in the 1990s, the golden age of beachboys existed primarily in memory and tradition. But Sammy’s work ensured that the values and practices of that era would continue through organized sports programs, surf schools, and cultural education.

Visiting Hawaii Today: The Steamboat Legacy

Modern visitors to Hawaii can connect with the Mokuahi family’s legacy in several ways.

Waikiki Beach

Waikiki remains the spiritual home of Hawaiian surfing and beachboy culture. The beach fronting the Outrigger Canoe Club, where Sam Sr. worked for decades, still offers surf lessons and canoe rides.

When you take a surf lesson or canoe ride at Waikiki, you’re participating in a tradition the Mokuahi family helped preserve. Look for operators who share Hawaiian cultural knowledge, demonstrate genuine aloha, emphasize ocean respect, and employ Hawaiian staff.

Outrigger Canoe Paddling

Thanks to Sammy’s efforts, visitors can experience outrigger canoe paddling through various clubs and tour operators. Many offer sunrise paddles, cultural tours, and racing experiences that connect participants to ancient Hawaiian ocean traditions.

The high school state paddling championship that Sammy fought to establish continues annually, giving hundreds of young people access to this cultural heritage.

Star Beachboys

Star Beachboys, co-founded in 1972 by Sammy and Arthur “Buffalo” Rutledge, continues operating today. Aaron Rutledge, Art’s grandson, leads the operation, working to maintain the beachboy traditions and get back to prime beach locations in Waikiki.

Supporting Hawaiian Culture

Honor the Mokuahi legacy by supporting organizations that continue their work:

Hawaiian cultural centers and museums that preserve beachboy history

Youth paddling programs that give the next generation access to traditional sports

Native Hawaiian education and language preservation efforts

Surf schools and beach operators that prioritize cultural education alongside athletic instruction

Why Sammy Steamboat Matters Today

More than fifteen years after his death, Sammy “Steamboat” Mokuahi’s story offers profound lessons about cultural preservation, giving back, and living with aloha.

Cultural Preservation Through Youth

Sammy understood that cultural traditions survive only when transmitted to new generations. His tireless work creating high school paddling programs ensured that Hawaiian youth would have institutional access to ancient ocean practices. This practical approach to cultural preservation offers a model for maintaining traditions in modern contexts.

Quiet Generosity

Sammy’s daughter noted that he “did a lot of stuff, but he did it quietly.” This humility reflects deep Hawaiian values of kokua (help) and malama (care) done not for reward but because it’s the right way to live.

Second Acts Matter

Sammy’s wrestling career made him famous, but his post-retirement dedication to paddling may be his most important legacy. His story reminds us that our greatest contributions might come not during our peak careers but in what we do afterward when we turn our experience toward serving others.

Living with Aloha

Throughout everything, Sammy maintained capacity for aloha. His consistent kindness, his quiet generosity, his decades of service to Hawaiian youth demonstrated that aloha isn’t situational or transactional but a complete orientation toward life and other people.

The Complete Legacy

Samuel “Sammy Steamboat” Mokuahi Jr. lived multiple lives: championship wrestler, beachboy’s son, surf instructor, and outrigger canoe paddling pioneer. But the thread connecting all these identities was his commitment to Hawaiian values and his dedication to passing traditions forward.

As Don Muraco said: “He was a good guy, quiet, dedicated to the community. He did a lot of work with canoe clubs in his community after wrestling.”

Every high school student who paddles an outrigger canoe benefits from the programs Sammy created. Every surf student at Waikiki who learns about Hawaiian culture alongside wave-riding technique receives an education shaped by the beachboy tradition Sammy preserved. Every young Hawaiian athlete who sees no contradiction between honoring traditions and achieving modern success walks a path Sammy helped clear.

E Ola Mau: May Life Continue

In Hawaiian tradition, we say “E ola mau,” which means may life continue, may it persist. This phrase captures the essence of what Sammy Mokuahi fought for throughout his life: ensuring that Hawaiian traditions, values, and practices would continue thriving for generations yet to come.

From his father’s beachboy generation through his own wrestling and coaching career, the Mokuahi family demonstrates how culture survives: through dedicated individuals who understand their kuleana (responsibility), who practice aloha daily, who build institutions that serve their communities, and who remember where they come from.

When you visit Waikiki and see beachboys teaching surfing, when you watch outrigger canoes racing across Hawaiian waters, when you encounter authentic aloha from someone who truly understands its meaning, you’re experiencing the legacy that Sam Mokuahi Sr. embodied and that Sammy Mokuahi Jr. preserved for future generations.

E ola mau ke aloha. E ola mau ka heʻe nalu. E ola mau ke hoʻokūkū waʻa.

May aloha live on. May surfing live on. May canoe racing live on.

Rest in Peace, Sammy Steamboat. The ocean remembers. The young people you helped remember. We all remember.

Sources and Further Reading

Sammy Steamboat Mokuahi Biography

SLAM! Wrestling: Sam Steamboat was a Hawaiian Legend

SLAM! Wrestling: Sammy Steamboat Profile

Honolulu Star-Bulletin: Wrestler Sammy Steamboat Promoted Paddling

WrestlingFigs: Sam Steamboat Passed Away at His Home in Hawaii

Find a Grave: Sammy Steamboat Mokuahi Jr. Memorial

Sam Mokuahi Sr. and Waikiki Beachboys

Honolulu Star-Bulletin: Sam Mokuahi, ‘Mayor of Waikiki,’ Was a True Legend

Find a Grave: Sam “Steamboat” Mokuahi Sr. Memorial

Hawaii Magazine: How Waikīkī’s Legendary Beach Boys Defined Aloha

OCC Sports: The Ka Mo’i Home at Last

KITV: Waikiki Beachboys Say They Belong Back on the Beach

Wrestling History

Cultaholic: Ricky Steamboat Details Where His Name Came From

Hawaiian Culture

This article honors Samuel “Sammy Steamboat” Mokuahi Jr. during Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian Language Month, February 2026). His legacy reminds us that cultural preservation requires dedicated individuals, that success need not compromise identity, and that the greatest achievements often come from quietly serving others.